| ||

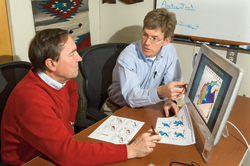

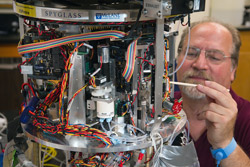

Moored at sea, the new instrument, called the Environmental Sample Processor, or ESP, samples seawater, filters out cells, and breaks them apart to release their DNA and telltale chemicals. It rapidly analyzes the DNA and specific chemicals to identify and count cells living in the ocean, and transmits the information in real time to scientists ashore, said Anderson, a senior scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). The ESP will be placed off New England's coast in spring 2011 and will act as both observatory and early-warning system, alerting researchers to the beginnings of blooms, or population explosions, of Alexandrium fundyense, a toxin-producing single-celled alga. Scientists now search for such harmful algal blooms (HABs) by chartering boats, taking water samples, and laboriously identifying and counting cells under a microscope. As a result, they can detect blooms only after they are already under way. The ESP will continuously monitor the water and detect blooms as they begin, days or weeks before current methods can. The toxins concentrate in algae-eating shellfish and fish and can sicken marine mammals or people who eat those shellfish or fish. Shellfish are routinely tested for contamination, and when a bloom occurs, shellfishing beds are closed to prevent contaminated seafood from reaching New England markets or restaurants. In recent years, harmful algal blooms in the Gulf of Maine and along Cape Cod have repeatedly caused closures and income losses to shellfish farmers. Made in Falmouth The ESP was developed over years by Chris Scholin, who was Anderson’s former graduate student in the MIT/WHOI Joint Program in Oceanography and is now president and chief executive officer of the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI). One of Anderson’s former postdoctoral researchers, Greg Doucette, who developed an ESP assay to detect toxins from another harmful algal species, will develop an assay for Alexandrium toxins for this ESP. Currently, the ESP remains on Anderson’s lab bench, where it has been renamed “Chris” in honor of Scholin. Using seawater samples brought to the ESP, WHOI researcher Bruce Keafer has been operating the instrument and “learning its ways,” he said, before they place it on a mooring in spring 2011. Although early models of the ESP were all built and used by MBARI researchers, the instrument at WHOI was built locally and is the first commercially built ESP. Next year's coastal ocean ESP placement will be the first long-term deployment on the East Coast, where it will provide the first fully remote observation of a seasonal Alexandrium cycle in New England waters. An advance in marine monitoringThe complex instrument required equally complex arrangements to bring it to WHOI. The instrument in Anderson’s lab was built by McLane Research Laboratories in Falmouth, Mass., with a license from Spyglass Biosecurity, and with MBARI’s collaboration. It was purchased by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and loaned to Anderson for use in his HAB studies in conjunction with the Northeast Regional Association of Coastal Ocean Observing Systems and state/federal partnerships to protect human and ecological health. Further support for this research itself is being provided by the National Science Foundation as part of the federal stimulus funding, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. McLane Laboratories will build five more ESPs in support of Anderson's plan to place them in strategic areas for Alexandrium detection along the Gulf of Maine coast. But this is just the start. Researchers have used early ESP models to detect other toxic algal species, and ESPs can also be used for detecting bacteria and larval organisms in the ocean. “You could use it to monitor sewage outfalls or pollultion in harbors and beaches, for example,” Anderson said. “The developers even hope it can go into space one day." Anderson's previous work on Alexandrium has been funded by NSF, NOAA, and Woods Hole Sea Grant, part of the NOAA Sea Grant College Program. —Kate Madin | ||

Search This Blog

Friday, December 10, 2010

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment